Change Your Image

R. J.

Ratings

Most Recently Rated

Reviews

The Final Cut (2004)

An infuriatingly wasteful mess of perfectly good ideas

Lebanese writer-director Omar Naïm's debut feature drops an intriguing, provocative premise: in the future, a memory chip can be implanted at birth and record a person's entire life experience, edited after death into a memorial film by a "cutter", described by one character as "part taxidermist, part priest and part mortician" for his ability to absolve the sins of the dead while presenting to the world a perfect facade. Robin Williams plays the appropriately named Alan Hakman, one such cutter, who finds in an editing job an image that sends him back to a childhood trauma and leads him directly into the moral quandaries involved in recording and editing memories that he had always shied away from. Naïm certainly doesn't shy away from those quandaries, but they're about the most interesting things in this debut that looks like a classy studio production, edited by veteran Dede Allen and lensed by Jonathan Demme regular Tak Fujimoto, but feels like a half-baked graduate project, with surprisingly amateurish scripting, acting and handling. Williams' subdued performance (much in the vein of the underrated "One Hour Photo") tries bravely to hold together what ends up as an infuriatingly wasteful mess of perfectly good ideas.

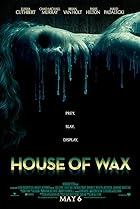

House of Wax (2005)

Sanitised yet effective "Texas Chainsaw Massacre"-type slasher

While the title will suggest this latest outing from producers Joel Silver and Robert Zemeckis' Dark Castle B-horror stable to be a remake of the 1953 3D classic starring Vincent Price, in effect it merely borrows the title and the central plot point of an eerie museum of far too realistic wax figures, then turns it into a sanitized yet effective "Texas Chainsaw Massacre"-type slasher, complete with backwoods redneck psychos, adroitly helmed by first-timer Collet-Serra, a Hollywood-based Spanish commercial director. Six twenty-somethings out to attend a varsity game in Baton Rouge get sidetracked by a detour and find an uncharted small town that seems suspended in time, its centerpiece a wax museum that is actually built of wax cue the usual dumb behaviour of twenty-something slasher fodder packs in horror movies, leading to their individual, painful and gory demise. Credit Collet-Serra and screen writing brothers Chad and Carey Hayes for attempting to inject some seriousness and character development into the project there's an interesting approach to sibling dynamics and the film's exposition takes twice as longer than usual, to properly set the characters up but, other than an engaging Cuthbert, a brooding Murray and a worthy villain turn from Van Holt, the casting is shallow and the inexistent talent of tabloid star Hilton hinders the film more than helps it. The unnecessarily lengthy running time is partially redeemed by a surreal and truly inspired climactic set-piece that's worth the price of admission alone.

Bewitched (2005)

Miscast screen version of classic sixties sitcom wastes intriguing premise.

Nora Ephron's hit-and-(mainly)-miss screen version of the 1960's hit TV sitcom starring Elizabeth Montgomery as a witch trying to become a normal American housewife has a marvelously clever twist as its starting point: it doesn't try to adapt the original format, but reinvents it by having as its premise a contemporary TV remake of the original series. The new "Bewitched" sitcom is a last-chance opportunity for washed-out star Jack Wyatt (Will Ferrell), who accepts to play hapless husband Darrin as long as a complete unknown is cast as Samantha and Wyatt finds her himself in a bookstore: the lovely and somewhat absent-minded Isabel Bigelow (Nicole Kidman), who has just arrived in town in search of love and has never acted in her life. But, just like Samantha, Isabel also happens to be an actual witch dreaming of a normal life... Although Ephron is an old hand at romantic comedy, "Bewitched" never really lives up to the intriguing premise Ferrell, more of a physical comedian, is painfully miscast, a radiant Kidman looks the part but doesn't seem to be in it, and most of the strong supporting cast goes mysteriously unused (a subplot that sees a charming Michael Caine, as Isabel's caddish warlock father, falling for Shirley MacLaine as her TV mother seems as if it was brutally hacked in post-production, as in fact most of MacLaine's role too). A wonderful sound-stage musical interlude to Frank Sinatra's "Witchcraft", shaped as a homage to classic MGM musicals, gives a good glimpse of the magic that Ephron failed to apply to the whole enterprise.

Zatôichi (2003)

Another disappointment from a director that may never have been the stylist we took him for

By this point I suppose most everyone will have given up trying to

understand cult Japanese director Takeshi Kitano's non-existant

career path - his two yakuza classics "Sonatine" and "Brother"

stand tall above the rest of a bafflingly eclectic oeuvre that reached

its commercial zenith with the slight but charming "Summer with

Kikujiro" and its nadir with last year's mystifyingly sparse "Dolls".

"Zatoichi" is yet another sharp left turn for the actor-writer-director,

here putting his own spin on the very popular title character, the

hero in a long series of pulp novels and genre movies. Zatoichi

(played by Kitano himself with hair dyed blond) is a master

samurai posing as a blind masseur, redressing wrongs throughout historical Japan, here helping a harassed village get

rid of the criminal gangs that rule it tyrannically. Unusually for

Kitano, who is a big TV star in Japan but as a director has never

grown beyond local arthouse status, this is in fact a made-to-order

job, since the series' usual producers specifically asked him to

present his own vision of Zatoichi. And it's a whimsical vision as

one would expect, as bloody and violent as his yakuza pictures but

lacking their gravitas, replaced with a deadpan sense of humour

too cynical or too dumb for the casual moments of poignant zen

poetry that Kitano scatters throughout. Above all, "Zatoichi" drags

where it should leap, is indifferently shot and edited (especially in

the fight scenes, where the quick cuts and slow motion effects

mask the obvious lack of choreography) and fails to evoke one

single time the excitement of the storybook adventures the

western-like tale practically demands. There are moments, but in

all this is yet another disappointment from a director that may

never have been the stylist we took him for.

Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003)

Rather good, actually - and perfectly in tune with the original cartoons' spirit

More than making up for the lame excuse for a film that was the

widely panned "Space Jam", this live-action/animation combination featuring Warner's cartoon characters perfectly

recaptures the classic Looney Tunes' wonderfully nonsensical,

freewheeling spirit. There isn't much in a way of an acceptable or

even decent plot, actually, but don't let that deter you since that's

precisely the reason why any attempt to fit the Looney Tunes gang

into a full-length film would flounder. Instead, director Joe Dante

and writer Larry Doyle erect a perilously teetering scaffold upon

which an insanely huge number of amazingly good sight gags and

verbal puns is set, while at the same time paying some sort of

warped tribute to classic sci-fi B-films of the fifties. The `plot' has

Daffy Duck fired from Warners by executive Jenna Elfman as

outdated, then proceeding to get security guard Brendan Fraser

fired along with him, and both embarking on a nutty drive to Las

Vegas to find the whereabouts of Fraser's dad, film star/spy

Timothy Dalton, eventually uncovering a dastardly conspiracy from

ACME chairman Steve Martin to use the Blue Monkey diamond to

enslave mankind. Of course it doesn't make sense, and that's fine

-- it's not meant to. You may point out that the live action/animation

combination doesn't always work, that the live actors never reach

the manic intensity of the cartoon characters (except for Joan

Cusack's wonderfully, ahem, daffy cameo), but really, that's beside

the point when the gratuitously violent and deliriously politically

incorrect free-for-all of the original cartoons is so perfectly

duplicated here.

Ying hung boon sik (1986)

Energetic but hardly faultless

It took Quentin Tarantino's seal of approval to make Hong Kong

movies hip to Western audiences, but Tarantino's protection still

can't disguise the many faults in John Woo's Z-grade thriller. The

schlocky, corny script could only have come from an Oriental idea

of an American movie, the music score is atrociously obtrusive

and both Leslie Cheung and Emily Chu overact hideously. But for

all that there's real energy in Woo's handling of the material: he

deftly side-steps the corn element to get the story chugging along

effortlessly, then concentrates on the virtuoso action scenes which

benefit from the tight editing and elaborate production lacking from

the rest of the film. That Woo is a master at filming action was

largely proven in his later Hollywood films, notably "Broken Arrow";

working with only a fraction of the budget, the results are less

impressive but equally arresting. However, you should definitely

avoid the English-dubbed version, which is not only appallingly

dubbed but also cuts five minutes from the Cantonese-spoken

original.

I Zombie: The Chronicles of Pain (1998)

The ultimate existentialist zombie movie

Andrew Parkinson's debut feature is a brave try at making the ultimate existentialist zombie movie, following a graduate student (Giles Aspen) infected by the zombie disease during a country walk and his progressive yielding to the hunger for human flesh. Intercutting "present-day" TV-style interviews with his girlfriend and the friends he lost touch with after his disappearance with his own experiences as he progressively succumbs to the primary urge to survive, there's much to admire in the straight-faced approach to the premise and in the bold clinical way in which Parkinson documents the gradual loss of Mark's humanity. Not surprisingly, the amateurish home-movie visuals (the film was actually shot in 16mm over a two-year period) lend some power to the conceit; the basic problem with "I Zombie" is that the script is insufficiently developed for a feature and should have stayed just under the hour-long mark. Alternatively you may try and see it as a laugh, but you'll be surprised just how quickly the laughs die down under the film's dark spell.

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002)

A surprisingly good directorial debut, if no masterpiece

Forget about George Clooney the "ER" heartthrob - after a string of films chosen for credibility over box-office and his producing investment with Steven Soderbergh in the risk-taking Section Eight company, his directorial debut is an equally risky proposition adapting a script that "Being John Malkovich" and "Adaptation" writer Charlie Kaufman had been touting around Hollywood for a while. Actually, the book on which it based is straight up Kaufman's alley: the allegedly "unauthorized autobiography" of TV producer Chuck Barris, creator of "The Dating Game" and "The Gong Show", where he alleges to have been a CIA contract killer in-between his TV responsibilities. Whether this is the actual truth (although, as would befit such a story, no proves can ever exist) or a figment of Barris' imagination is left to your own, and this is perfect fodder for Kaufman's favourite subject: reality as opposed to illusion, what constitutes truth and lie, where do we draw the line and how far can we go with it, and how much does perception shape it. Basically, though, it's a film about a little boy lost desperately looking for a way to fit in and overcome his need for love, as effectively presented in Sam Rockwell's strong performance; the fact that it's a story about a TV personality who spent his life reaching for heights, crashing and burning and then coming back for more may have also been a factor in Clooney's choice. However, despite the script's cleverness and Clooney's great way with actors (single-handedly rescuing Rutger Hauer from B-movie limbo with a poignant supporting performance and extracting charming against-type moments from Drew Barrymore and Julia Roberts), his stylized, saturated widescreen compositions, while perfectly in sync with the general outlandish tone, are far too polished and stylish for Kaufman's unconventional script. This is as assured as directorial debuts go, but no masterpiece.

Daredevil (2003)

Routine comic-book action, effectively filmed

Disregard the almost universal critical panning Mark Steven Johnson's big-screen adaptation of Stan Lee's blind comic-book hero received at the hands of US reviewers - while no great shakes and a very blatant attempt at a controlled-budget knock-off of "Spider-Man", this is in fact a pretty honest and technically well done film version. The first half hour is mainly exposition, taking neophytes through their paces as we learn how the son of an Hell's Kitchen boxer, blinded in a freak toxic waste accident, compensates for his loss with an acute development of the other four senses and grows up to become a high-minded lawyer with a nights-only sideline as a vigilante prowling the streets to serve justice on those who elude the law. Good exposition it is as well, effortlessly making the hero credible and setting him in a credible world. At some point, however, it all falls into comic-book unreality as expected, but taking itself so much more seriously than it should that you're aching for the action setpieces to come up. The film's basic claims to greatness lie in its clever visualization of the hero's blindness - "seeing" the objects through X-ray-like soundwaves - and in Colin Farrell's out-of-control cameo as the psychotic assassin Bullseye; everything else is routine comic-book action, effectively filmed.

National Security (2003)

A perfectly acceptable action comedy

It's "48Hrs." territory all over again in Dennis Dugan's disposable but enjoyable buddy cop comedy: by-the-book beat cop Steve Zahn and would-be cop Martin Lawrence can't stand each other and yet end up teaming together, as security guards, to unmask a mysterious gang of violent robbers responsible for the untimely death of Zahn's beat partner. No points for originality or subtlety in TV's "Spin City" writers Jay Scherick and David Ronn's formulaic script; but it does allow Lawrence and Zahn to develop an offbeat, often very funny opposites-attract chemistry underlined by a race-card subtext that applies equally to blacks and whites. And Dugan, a former TV actor and director, never loses sight that the film lives or dies on the basis of its stars, so he lets them run off with the material while reining them in just enough to keep them under control. A perfectly acceptable action comedy.

Frida (2002)

A biopic with its heart on the right place

Julie Taymor's biopic of the revolutionary Mexican artist Frida Kahlo isn't as eccentric and daring as her stunning take on Shakespeare's "Titus", but is still a subversive and engaging picture, content to let the wild and wondrous tale of Frida's eventful life speak for itself. Crippled in her teenage years in a horrifying bus crash that would leave her in pain for the rest of her days, Frida is here presented as a pioneer free spirit that assumed her unorthodox ideas in the mid-twenties; although coming from a well-off bourgeois family (nearly bankrupted by the constant operations her disjointed body required), she embraced communism early on, painted in a extremely personal faux-naïf style with surrealist overtones while all around her political art was all the rage, enjoyed a healthy bissexuality (a lesbian tango scene is downright smouldering) and found the love of her life in a tempestuous marriage to notorious womanizer and artistic luminary Diego Rivera. Much to Taymor's credit, but also to Salma Hayek and Alfred Molina's passionate performances (why only Hayek was nominated for an Oscar is beyond me), "Frida" not only engages you in this exotic rollercoaster ride that wears its heart proudly in its Latin sleeve, it also gives you a sense of passing time, of opportunities lost, of magic in the making. While Frida was an artist, this isn't a film about her art, but about her life and the way she turned it into her art, gracefully underlined by Taymor's resort to animated interludes where the paintings seem to come to life (through CGI animation or old-fashioned montage or puppetry). That's why it's a shame that the script is so conventionally plotted and that the film's conclusion seems strangely subdued after the celebratory mood of what's come before. But these are minor quibbles, since "Frida" is that rarity of rarities: a biopic with its heart on the right place.

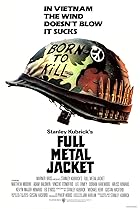

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Harrowing, chilling, idiossyncratic take on the Vietnam war

Stanley Kubrick's take on the Vietnam war is typically chilling and idiossyncratic, following a Marine platoon from basic training at Parris Island to actual combat during the Tet offensive; but it's the training sequences (the film's first half) that everyone remembers, thanks to the superb performances of Lee Ermey as the brutal drill instructor sergeant and Vincent d'Onofrio as the "odd man out" that he picks on and eventually leads to a violent breakdown (Ermey was an actual Marine instructor and had originally been hired as the film's technical advisor - then Kubrick got the inspired idea of casting him in the role). The film's muted reception wasn't helped by its timing - after "Apocalypse Now", "The Deer Hunter" and "Platoon", it didn't seem at the time as if Kubrick had put a new spin on the subject. With hindsight, however, the film is as harrowing as any of its predecessors, tracing as it does the de-humanisation of the soldier, his transformation into a killing machine, and following it to its logical conclusion, the war theatre, to see how it all turns out (not surprisingly, the only soldier whose real name we are told instead of its military handle is the only one that never makes it through the training). Majestically directed and photographed, and surprisingly shot entirely on British locations.

Car Wash (1976)

Not much of a film, but endearing nonetheless

Seen in retrospect, there doesn't seem to be much to recommend Michael Schultz's flimsy mosaic comedy about a Friday at the Deee Luxe Car Wash in Los Angeles, a huge box-office hit of its time with a virtually all-black cast soundtracked by Norman Whitfield's groovy disco score. In fact, though, "Car Wash" paints a peculiarly disenchanted portrait of race relations in America in the mid-seventies: although there's no racism invoked throughout, the car wash is owned by Jewish entrepreneur Sully Boyar but almost entirely staffed by ethnic minorities (the exceptions are Texan pump attendant Jack Kehoe and suburban receptionist Melanie Mayron), and the mostly black staffers comprise nearly every single stock black character of American movies - the aspiring soul singers (Darrow Igus and DeWayne Jessie), the gay (Antonio Fargas), the ex-con (Ivan Dixon), the radical Muslim (Bill Duke), the clumsly loverboy (Franklyn Ajaye), the aged shoeshine (Clarence Muse). Unlike most other movies, though, the great ensemble cast manages to turn these stock characters into living, breathing people, with pride, dignity and joy, within the very limited frame. And Joel Schumacher's (yes, that Joel Schumacher) script actually avoids some of the race pitfalls - the drop-out bong smoker of the lot is the white owner's son (a hilarious Richard Brestoff), given to quote from Mao's Little Red Book at every instance but totally unaware of the actual significance of the theories, and the "villains" of the piece are black people: the policeman that "checks" on ex-con Dixon, the televangelist of the "Church of Divine Economics" (Richard Pryor) that gets rich off the oh so many gullible brothers. As a motion picture, it's only slightly above TV movie level (as most of Universal's mid-seventies B-level pictures, mostly made by directors trained on TV, were); but as a sociological document of an era in American society, it's flawless.

La peau douce (1964)

A stunningly modern film on the most classic of all melodramas

François Truffaut's fourth feature and his first true masterpiece is essentially a classic love triangle, filmed like a quiet juggernaut that eventually overwhelms all those involved. On a quick trip to Lisbon for a lecture, literary essayist Jean Desailly's eye catches the lovely Françoise Dorléac, the air hostess on his flight. Soon he's asking her out for a drink and a love affair develops in between her flights, as his married life with seductive but demanding wife Nelly Benedetti slowly unravels. Much to Truffaut's credit, there is no judgment passed on any of the characters: whether Desailly is undergoing a dreaded mid-life crisis and wishes to be young again or is merely indulging an intellectual whim, whether he really wants to prove himself he is still a man capable of passion or just looking for a way out of his stifling marriage, is entirely up to the viewer to decide. But the director doesn't avert his eye from the seedy unpleasantness of the central situation, as the masterfully extended Reims interlude and the shock ending prove. Basically, it's a film about the mess people make when they think they're in love, all the more disturbing because Truffaut bases it all on chance meetings and missed opportunities - had Desailly not arrived late for his plane to Lisbon, had Dorléac not called him back at the hotel, maybe none of this would have happened. Marvelously shot in black and white by Nouvelle Vague lenser Raoul Coutard, this was the very first film where Truffaut showed the world all he was capable of; it's a stunningly modern film on the most classic of all melodramatic stories.

Cat People (1942)

A modern classic

Jacques Tourneur's low-budget horror B-movie about a young woman of Slavic ascent haunted by what may or may not be a folkloric curse seems pretty tame by today's standards, but was in fact a revelation at the time of its release thanks to its reliance on mood and atmosphere, having been the first film to avoid depicting its "monster" and work exclusively within the realm of suggestion. All-American boy Kent Smith meets the lovely Simone Simon in the zoo, where she is seen sketching a panther; soon they're madly in love with each other, but she is haunted by the folk tale of her village, whose descendents are cursed to turn into cats and kill the man they love. The plot seems downright naïf these days but the subtext, playing with repressed love and sexuality, and even toying with the then-emerging field of psychiatry, is as potent as ever, especially when stylishly, languidly enveloped by Tourneur and cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca in a high-contrast, textured black and white photography. The acting is generally dismal, but other than that "Cat People" pretty much explains why the low-budget limitations of B-movies have been so influential in the development of modern genre cinema: it's a modern classic, although contemporary filmgoers may attach more importance to its historical value than to its entertaining qualities.

Pinocchio (2002)

Never so much has been so wasted

Never so much has been so wasted as in hyphenate Roberto Benigni's ill-advised live-action version of Carlo Collodi's much-loved classic. Allegedly the most expensive film ever made in Italy - a $45 million extravaganza entirely shot in lavish stage sets -, this Pinocchio stays pretty close to Collodi's original dark fable of a naïf, mischievous wooden puppet whose greatest desire is to become a flesh-and-blood boy, avoiding the Disney whitewashed version. But that, along with Benigni's wife (and co-producer) Braschi's lovely performance as the Blue Fairy and the late Danilo Donati's wondrously whimsical production design and wardrobe, is about all you can recommend in the picture. Everything else is a mistake: plodding, pedestrianly handled, "Pinocchio" is a painfully dull, style-less pageant, failing to make the most of such impeccable production values and with Benigni's shrill, hysterical performance, wholly inadequate, totally missing the story's point. Fellini once dreamt of directing the story with Benigni in the role; more's the pity that he did not get around to do it and left Benigni to do the job so unsuccesfully. It's probably unsurprising that the film was a huge seasonal hit in Italy; but it's hard to see how anyone else, especially since the much beloved "Life Is Beautiful", will even begin to like it.

The Dancer Upstairs (2002)

A promising debut

A curious but not entirely unexpected idiossyncratic choice from John Malkovich for his directing debut, this adaptation of Nicholas Shakespeare's novel fictionalising the capture of the leader of the Peruvian Shining Path revolutionary movement is a more pensive, less political throwback to the European "political thrillers" of the 1970s made popular by directors such as Costa-Gavras. Malkovich, however, dislocates the film's centre from politics into personal mores, following the story of Javier Bardem, as the police detective assigned to discover the whereabouts of the mysterious terrorist leader "Ezequiel". In a superbly controlled performance, Bardem emphasizes the vulnerability of this disenchanted, seen-it-all cop thrown against his will into the frying-pan and the way he attempts to maintain his dignity and uphold the law he no longer believes in. Malkovich proves an engaging director - despite its lengthy running time (and although it could use a slight trim), the film is neither predictable nor overstays its welcome, and the actors deliver consistently good performances. One wishes Malkovich had looked for a better story to tell, but as debuts go this is a promising one.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970)

Thoroughly civilised, delightful entertainment

Billy Wilder's take on the world's most famous detective is both painstakingly faithful and sardonically subversive to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's idiossyncratic creation. Presented as a case that loyal companion John Watson duly recorded but requested remain secret until long after his death, in which Holmes aids a Belgian woman find her missing husband, a mining engineer hired by an apparently non-existant English company, it makes clever use of the rulebook Conan Doyle set down while at the same time undermining it from within. The title and the plot may seem misleading at first - the first half hour especially seems at odds with what comes afterwards - but in fact if you're a Holmes fan you'll quickly realise that this is as close to romance as the detective would ever allow, and Wilder tells it through a masterful accumulation of small touches that only someone as meticulous as the man himself would notice. Script-wise, it's a cracking mystery in the best Doyle tradition, with all the time-honoured twists and turns present and correct. The acting is also up to Wilder's usual standards; Stephens and Blakely are an engaging duo as a bored Holmes and a bumbling Watson, and there's a hysterically funny supporting turn by the always underrated Revill as a Russian ballet impresario. Wilder's trademark pointed cynicism fits the English witticism particularly well, even if at times it all seems a bit too modern for the peaceful Victorian surroundings, but it is quite ironic to see him chiding Britain's stiff-upper-lip, old-fashioned morality when the film seems to be an "old timers' movie" entirely out of sync with its own time. Still, it's hard to find fault in such a thoroughly civilised and delightful entertainment.

Two Weeks Notice (2002)

Disheartening romantic comedy that fails to run off with a great premise

A good romantic comedy is something very hard to pull off successfully, and "Two Weeks' Notice" is proof that, when you don't pull it off, the results can be disheartening. Despite the presence of certified genre stars as Hugh Grant and Sandra Bullock, this directing debut from "Forces of Nature" and "Miss Congeniality" screenwriter Marc Lawrence, also masterminded by Bullock's Fortis Films company, fails to actually run off decently with its potentially great Cinderella premise: an idealist, activist lawyer accepts to work as legal counsel for a jetsetting millionnaire who treats her as a personal assistant, and eventually resigns from her job only for both of them to find letting go is not as easy as they expected. The script was probably very funny but it must have got lost somewhere in the filming, as not even Susan E. Morse, who edited Woody Allen's films for nearly thirty years, manages to help Lawrence find it. There is the occasionally inspired gag and the typecast stars make for an easygoing, charming couple, but the fairytale mood never really crystallises and you?re left with a pretty forgettable entry.

Chicago (2002)

Good, but Bob Fosse would have made it better

It's hard not to look at this long-delayed big-screen adaptation of Bob Fosse's Broadway hit musical and think how much better it could be, had the late Fosse himself directed it, as he'd originally meant to. What we have, though, is a very effective, professional and honest rendering of the show, underlining its cynical, prescient take on fame and the media. In 1929 Chicago, aspiring but talentless chorine Renée Zellweger kills a lover who'd wrongly promised her a shot at the footlights, and finds out that her crime of passion may just be the ticket for the big-time she needed in a town where murderers - especially if they're female, vaguely scandalous and very good-looking - are as big as movie stars. "Gods and Monsters" director Bill Condon's script revises the plot, making the musical numbers imaginary projections of Zellweger's surroundings, turning her bleak prison world into a stage of the mind, in an attempt at making the stage-bound conventions of the genre work for audiences less likely to suspend their disbelief today as they were at the musical's heyday. But ultimately this is no "Moulin Rouge", since choreographer and first-time director Rob Marshall means to update a hit stage show for the screen rather than reinventing the musical for modern generations. John Kander and Fred Ebb's stupendous songs are carried through to the film without any attempt at making them sound more contemporary, and the only link between Baz Luhrmann's extravaganza and Marshall's lean, streamlined filming is the cast of "regular" movie stars required to sing and dance, something they do with gusto and an often surprising talent - although Richard Gere's casting as a rakish, money-grabbing star lawyer is inspired, allowing him to make fun of his own image as a hunk, it's Catherine Zeta-Jones's sensuality and ease on the musical numbers and John C. Reilly's suffering, betrayed husband who take the film home. Solid entertainment, but nothing to shout home about and certainly not worthy of its 13 Academy Awards nominations.

The Hours (2002)

Prestige job? Yes - but an impeccably tasteful one

On paper, Stephen Daldry's adaptation of Michael Cunningham's immensely acclaimed novel had everything going against it, reeking of Hollywood prestige job tailor-made for Oscar season - and its nine nominations only seemed to underscore it. In practice, however, Daldry and writer David Hare have made a stellar job of translating the novel's defiantly literary devices into film. Cunningham's book applied the central device of Virginia Woolf?s novel "Mrs. Dalloway" - a woman's whole life condensed and allegorized into one single day - to three alternately told stories: that of Woolf herself as she begins writing the novel in 1923, that of a depressed 1951 L. A. housewife who begins reading it, and that of a 2001 NY book editor nicknamed "Mrs. Dalloway" by the now-dying love of her life. Subtly, sensibly and stylishly drawing the parallels through the three stories by purely cinematic means, stage veteran Daldry signs here an immense leap forward from his debut feature "Billy Elliot" and manages to transcend the prestige job façade, turning "The Hours" into an elegantly told, melancholy melodrama about sorrow and loss, for its three central characters all mourn something they have lost irredeemably but still yearn to recover with all their forces "the history of who they once where". Meryl Streep (the editor), Julianne Moore (the housewife) and Nicole Kidman (Woolf) are all stellar and ably backed by a wonderful supporting cast (full marks for the reverse typecasting of Ed Harris and Jeff Daniels), while Philip Glass's lushly romantic minimalist score underlines the film's intensity and passion. We'd be so much better off if all prestige jobs were as good as this.

Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

Original, touching and absolutely brilliant

The film that should for all purposes confirm "Magnolia" director Paul Thomas Anderson as one of the most exciting, original and inventive of modern American filmmakers, "Punch-Drunk Love" is a marvellously quirky romantic comedy of sorts that is constructed like a classic Hollywood musical without the songs and throws you a curveball at every conceivable turn. While being a romantic comedy, it is also a bitter-sweet, stylized meditation on love and loneliness and one of the sweetest melancholy tone poems you're likely to see on screen. The film centres around Adam Sandler, with Anderson typecasting him as his usual man-child persona but digging well beneath the surface to bring out his dark side and his humanity. The head of a small toiletries company, Sandler's Barry Egan is a naïf, disturbed boy, reeling from a life spent in the shadow of seven prepossessing sisters and wanting to stand up for himself in the world, but who sees it from an entirely different perspective. "Punch-Drunk Love" tells the story of how he finally meets his equally dislocated soulmate in the luminous Watson, as he exploits a loophole in a frequent-flyer pre-packaged food promotion and grapples with an harassing sex phone line operator. Exquisitely photographed by Robert Elswit in bright, ravishing colours and propelled by Anderson's fluid camerawork, the film's construction - punctuated by Jeremy Blake's garish, colourful artwork interludes - seems to flaunt every conceivable law of narrative logic and structure, but that's alright because that's the way Anderson works: you just don't expect an average romantic comedy from the guy who directed "Magnolia", and this is so much above the average that is in risk of creating something altogether different and new. Original, touching and absolutely brilliant.

Adaptation. (2002)

An outrageously grandiose accomplishment: a masterful film about itself!

If you thought "Being John Malkovich" was weird, chances are you'll find the follow-up collaboration between pop video whizkid director Spike Jonze and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman even weirder, making this proposed adaptation of Susan Orlean's non-fiction best-seller "The Orchid Thief" one of the most bizarre films ever financed by a major studio. For starters, it's not really an adaptation of the book, but rather about the adaptation of the book: this is in fact the story of how screenwriter Charlie Kaufman attemped to write a script adapting Susan Orlean's book and of the mess he gets involved in while doing it. And yes, Kaufman has written himself and all of the real-life characters around the story - Orlean, her subject and orchid-obsessed horticulturalist John Laroche, screenwriting guru Robert McKee - into the story, then has them played by actors and makes them do stuff they never actually did in real life, and invents himself a twin brother who is also credited as co-writer of the finished film. All of this while contemplating the difficulties of adaptation, both in its evolutionary sense and in its Hollywood sense of translating a book into film; "Adaptation" is probably one of most self-obsessed and self-absorbed films ever made - it's a film about its own making - and yet it is an absolutely engrossing study of that one spark of human creativity from which any sort of emotion - hence of art - evolves. Needless to say, it's a pain to explain in writing what the film is all about, but you follow it pretty well on screen thanks to Jonze's effortlessly clear direction. In fact, Jonze replies to the script's chinese-box self-referential structure by simply shooting it straight-forwardly, letting the momentum take care of it. However, its more cerebral tone (this is, after all, a story about a screenwriter's block) means it's a bit more heavy-going than "...Malkovich". Nevertheless, it's an outrageously grandiose accomplishment: Jonze and Kaufman actually pulled it off. One of the most original and enjoyable major-studio films in recent memory, and a field day for cinema theorists.

Maid in Manhattan (2002)

Classic fairytale romance - not a great romantic comedy, but not bad

What, you might ask, are "Smoke" director Wayne Wang and "Spider" star Ralph Fiennes doing in, of all things, a romantic-comedy vehicle for Jennifer Lopez? The cynical answer would be earning their rent, of course, but unlikely as it may be Wang actually pulls off this formulaic Cinderella story of a Latino hotel maid mistaken for a fellow guest by a handsome tony politician running for Senate who falls madly in love with her, turning it into a engaging and utterly charming romantic comedy. The wondrous part is, "Maid in Manhattan" had everything going against it: originally written by John Hughes as a starring vehicle for Julia Roberts, who declined to star in it but remained involved through her production company, the film suffered a number of rewrites once Lopez came on board, eventually leading Hughes to cut his ties with the studio and withdraw his name from the credits, and was still undergoing rewrites as it went into production. It only shows in the rather hurried ending, since everything else is classy, classic fairytale romance, much helped by Wang's discreet handling, a solid supporting cast and two charming performances from the high-chemistry leads: Lopez, though typecast as the confident Latina, is particularly good, and Fiennes shows a lighter side of him that serves him well. While not one of the great romantic comedies, it's the best of what has been a very lacklustre season for the genre and a sweet, worthy entry.

Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi (2001)

No other way to describe it: A masterpiece

By now Japanese anime master Hayao Miyazaki must be animation's best-kept secret; Pixar's John Lasseter and any number of Disney animators simply revere him, the venerable Mouse House has even decided to help finance him and 1997's "Princess Mononoke" raised his Western profile. For all of that, though, Miyazaki is still a secret and it would be a shame that, because of it, this touching and incredibly powerful fantasy shouldn't find the international audience it rightfully deserves. Not that Miyazaki is that bothered about it, since "Spirited Away" has become the all-time Japanese box-office champ, was the first animated film to win the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and had already cleared $200 million in international box-office before even opening in America (in France alone the film played to two million viewers). Basically, "Spirited Away" is a modified fairy-tale in the Japanese tradition, following the adventures of ten-year old Chihiro, a moody, spoilt young girl who finds herself trapped in the world of Japanese gods and spirits after her parents take a wrong turn with their car. The only way out of a dismal fate for the girl and her parents is for Chihiro to work in the bathhouse of the gods, where she will live through a series of fantastical adventures. Although what I've just written may make it seem childish, the story is practically unresumable and a lot more strange than it seems, recapturing the edgy nature of the earlier fairytales without ever allowing violence or wickedness inside; even so, it's probably good to leave younger kids at home since some of the images are far too weird for easy explanation. The film works best as a Japanese version of "Alice in Wonderland" without the witticisms and with an added heart, and is directed by Miyazaki in an effortlessly painterly style that enchants and intrigues at the same time. From its rather non-descript beginnings, "Spirited Away" develops into a moving parable about learning to know yourself that surprises you at each turn and ends up tugging your heart strings as much as it can without ever yielding to any sort of concessions. There's no other word: this is a masterpiece.