Change Your Image

kinoreview

Reviews

Mission: Impossible - Fallout (2018)

Impressive, but not involving.

Mission: Impossible - Fallout impressed me, but it did not involve me. The stunts and set pieces are indeed a sight to behold, but the story and characters are so utterly generic that it becomes a rather detached exercise of 'I wonder how they did that?'. It's as if they began by storyboarding the set-pieces and then assembled the hackneyed premise as a perfunctory afterthought.

Again, the set pieces are amongst the best in the business, but sometimes even these fail to impress, especially some of the combat. The problem is that in the world of Mission: Impossible, everyone has superhuman powers of strength, agility and recovery; we see a litany of characters, both men and women, beat the hell out of each other with an absurdly gymnastic style of violence that's so bereft of consequence that it wears thin by the film's second burst of tiresomely frenetic melee. As the The Raid series demonstrates, fighting, even amongst the highly-trained, is a nasty, brutish affair - not a balletic, bloodless spectacle of flying kicks and spinning torsos.

This isn't the film's undoing, however, and neither is the trite plot, the real drag is the character work. Fans of the franchise will no doubt welcome the familiar faces and enjoy their chemistry, but to the uninitiated (i.e. Me), the IMF crew were so-so, and several antagonistic characters, namely Erika Sloane and the White Widow, were smug in a decidedly charmless manner.

Still, despite the negative tone of this review, Mission: Impossible - Fallout is not a bad film, just an overrated one.

Annihilation (2018)

Self-important B-movie

Annihilation riffs on Stalker, Predator and The Thing and manages to be worse than all of them, even Stalker, and that was really boring.

The problem is that Garland's script is more interested in the science fiction of 'The Shimmer' rather than the characters, so we end up with Lena (Portman), the bland protagonist; Dr. Ventress (Leigh), the insufferable team leader with a smugly nonchalant demeanour; Anya (Rodriguez), an aggressive, thuggish stock character; and Josie (Thompson), a bookish non-entity. There was one other, I think, but when the characters are this disposable, who cares?

There is little to make up for this dearth of character and chemistry; we get some sense of adventure and a few thrills and scares but in each case they are fleeting and mediocre. Instead, we get a bit of jumped-up B-movie science fiction that's presented in a miserably glum, portentous manner. Also, the CGI has a distinct lack of tangibility and is thoroughly overused.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017)

An engrossing drama that's marred by crude dialogue, dubious casting and wayward narrative shifts

The first thing that must be said about Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is that it is a step in the right direction for Martin McDonagh. Everyone loved In Bruges, it was a perfect blend of the dark and the humourous, and it had a lot of heart, too. However, that pathos was lost in his sophomore feature Seven Psychopaths, which favoured cineliterate metafiction and frivolous pop-culture gags.

A cursory read of the synopsis will tell you that Three Billboards is more than a return to the dark tragedy of his debut. Indeed, just the title suggests that McDonagh has once again made the location of his story a character in itself, only this time we have the verdant mountains of the Deep South (it was filmed in North Carolina) rather than the spires and canals of medieval Bruges.

This sweeping backdrop is stage to a vicious yarn about small town America and small town attitudes. In short, it is about Mildred, a tough, belligerent woman who uses a provocative message spread across three billboards with the aim of reigniting the search for her daughter's murderer(s). Again, Mildred doesn't suffer fools gladly, but just when you think that there are no cracks in her granite veneer, the textured interplay of McDonagh's characters start to reveal them. This is especially true of Mildred's relationship with Sheriff Willoughby, which, despite all the public mud slinging, has an underlying respect and mutual schadenfreude sense of humour. Their chemistry has a particularly poignant depth when Mildred swiftly drops her prickly facade to comfort him in a desperate moment. Scenes like these are the highlights of Three Billboards.

However, there are several problems with the film both small and large. Firstly, there's too much swearing. It may well be an honest depiction of the way these people speak, yet much of the incessantly crude language seem to be played for the laughs, and it didn't elicit many from me. Secondly, there are several questionable castings, namely Abbie Cornish - who is too young and too Australian to be a credible wife to Woody Harrelson's characte. Even more egregious is Samara Weaving's performance as Penelope, the stupid young girlfriend of Mildred's white trash ex-husband. Again, she is just not credible; a girl with her kind of wholesome attractiveness just wouldn't be with a scummy lowlife like Charlie - she needed to be brassier. The worst thing about her character, though, is how flatly written she is. In fact, she's not a character but a cheap, ditsy punchline delivered with wide-eyed obviousness.

The third and most problematic issue, however, lies with the narrative. There are two important acts of violence in the film, Jason Dixon's brutal assault of Red and Mildred's firebombing of the police station. One can see how these violent set-pieces serve as the nadir of the each character's tempestuous personality, but they largely go unaccounted for. These are both serious crimes, yet Jason merely loses his job and Mildred is barely even questioned; I'm sorry, but such drastic crimes would have interrupted and overruled whatever was happening beforehand. Some may argue that such narrative matters should be overlooked, but credibility matters.

These flaws prevent Three Billboards from entering great movie territory, but Martin McDonagh's third effort remains a well-acted and engrossing drama that sometimes hits the same darkly humourous notes of his superb debut.

La tortue rouge (2016)

Ponderously self-important

The ambience and immersion created by the graceful animation and punchy sound design quickly wears thin as The Red Turtle reveals itself to be a ponderously self-important work. The curious decision to avoid dialogue altogether makes it quite difficult to care about the hollow little figure at the centre of it, and the heavy use of metaphor doesn't help ratchet up the emotional appeal, either. I spent most of the running time wishing I was watching Cast Away or even that similarly laconic sea adventure All is Lost.

Brief Encounter (1945)

A timeless tale of heady, all-consuming romance,

It may be 72 years old, but Brief Encounter's tale of heady, all-consuming romance is timeless. In fact, the film's character driven narrative is bolstered by its quaint, wholesome and passionately sentimental charm.

Celia Johnson (Laura) and Trevor Howard (Alec) deliver performances that are just as sensitive and articulate as Noel Coward's poignant, eloquent script. Johnson is particularly impressive in the way she tactfully skirts the overwrought potential of her character with a performance that is nuanced as it is endearing. The stellar leads are also supported by several interesting characters, especially Myrtle the sassy cafe manager and Albert the cheeky station conductor.

Perhaps the only criticism of Coward's pithy script is that it doesn't sufficiently develop Laura's relationship with Fred, her seemingly mild-mannered and understanding husband. More detail of her staid, suburban existence may have given her romantic dilemma even greater resonance.

Minor gripes aside, this proverbial classic is likely to cause a lump in the throat of anyone who has experienced the difficult, overwhelming feelings of Laura and Dr. Alec.

Free Fire (2016)

An eye-rollingly childish waste of time,

Wheatley continues to underperform with this tedious piece of juvenilia. It's bereft of the insidious tension that made Kill List so gripping and sorely lacks the heart, humour and offbeat charm of Sightseers. All Free Fire has is an adolescent script and a slew of utterly hollow characters in 70s fancy dress. As other reviewers have commented - you wish they'd just hurry up and kill each other.

Amadeus (1984)

Amadeus is an entertaining if factually dubious biopic

At the heart of Amadeus's narrative is Antonio Salieri's jealous admiration for Mozart's prodigious talent, with the wider meaning being about unearned privilege and power attempting to control and hinder creative genius. The most odious example of this is Count Orsini-Rosenberg (Charles Kay), the Emperor's most pompous little minion.

It's also a film about the selfishness and immorality of faith, as shown in Salieri's obsessive behaviour and the faith he uses to explain it. Salieri, who jokes that he is the 'patron saint of mediocrity', believes that God gave musical genius to a crude, immature young man like Mozart just to spite him. Blinded by his self-absorption, it doesn't occur to Salieri that his anxieties are trivial and insignificant because he believes God is omnipotent - 'He' can listen to everyone's concerns no matter how trivial they are. So on the delusion continues...

The film's main strengths are the leading performances from Abraham and Hulce, the opulent design work and the flashback narrative construction. This combination makes for a very absorbing film for the first 120 minutes or so, but Mozart's quite sudden decline did lose me somewhat. Could bereavement and a challenging project really cause such a spirited young man such damage? Well, it's little surprise that his decline would seem dubious because Mozart's mysterious death remains the subject of heated debate.

Criticisms are few and minor. Some of the language is rather inappropriate for a film set in the high-society of 18th century Vienna -would Mozart really have said "kiss my ass"? Also, the film's authenticity was wounded by the American accent of Tom Hulce, who otherwise does a great job.

The Believer (2001)

Gosling's transformative turn remains one of his best

The Believer is narratively so-so but both the dialogue and Ryan Gosling's performance are excellent - Gosling is transformative. This caustic little indie doesn't pack the punch or production values of American History X, but Tony Kaye's film is something of a glossy, melodramatic morality tale. Instead, The Believer focuses not on slick monochrome cinematography but on the psychology and philosophy of anti-semitism. The film is at its best when Gosling delivers the venomous yet articulate diatribes of Henry Bean's script, which offer compelling insights into the toxic mix of paranoia and fury that fester in the anti-semitic mind.

Jackie (2016)

The deliberate pacing may test your patience, but Jackie remains an authentically personal account of an infamous crime

It doesn't matter who you are or how much privilege you enjoy, having your spouse murdered so brutally beside you is a monstrous tragedy. Jackie captures the pain, both sharp and bleak, that the First Lady must have experienced during and after her husband's assassination. A particularly poignant moment is when Jackie sobs as she wipes the blood from her face; it is her first moment alone since the horrific shock of her life-changing trauma. However, her character becomes less sympathetic as she reveals a prickly demeanour with a tendency to be difficult. Not a diva by any means, just a bit unnecessary.

The performances and period detailing are excellent, but Pablo Larrain's deliberate pacing is just a little bit too slow. It gets to the point where the repeated shots of Jackie's withdrawn doe-eyed face elicit annoyance rather than pathos. At 1hr 40 minutes, Jackie is not a long film, yet it could have and perhaps should have been even shorter. Perhaps the editor's scissors could have been taken to the sequences with Jackie's priest (John Hurt), which consist largely of asinine religious musings. Then again, Catholicism was more important to the Kennedys than it is to me.

Even with the pacing issues, Jackie remains an authentically personal account of an infamous crime.

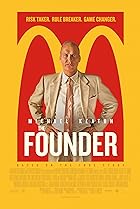

The Founder (2016)

Robert Siegel spins compelling source material into an entertaining romp of a biopic,

The Founder is an entertaining and well-paced biopic with a lush colour palette, charming period details and a wired performance by Michael Keaton. Although the spectre of cliché and formula can be felt, they never fully arrive because of the skillful brevity of Robert Siegel's script, which pithily packages McDonald's origin story and creates a reasonably complex character in Ray Kroc. He's introduced as a motormouth salesman with a strained marriage, yet he transcends this stock character and earns our sympathy through his cast iron perseverance and lack of pretension. This sympathy, I hasten to add, all but evaporates as Kroc becomes more and more of a parasitic usurper.

Again, there are times where you sense the arrival of a contrived plot point or two, but The Founder confidently skirt mediocrity through the strength of its performances, cinematography and compelling source material.

Mother! (2017)

A decidedly inferior homage to Rosemary's Baby that amounts to little more than a series of pretentious metaphors and allegories

I can absolutely understand why someone would dislike or even hate this film, but let's start with the positives. Firstly, the sound editing is excellent; you hear every footstep and creaky floorboard in the imposing, shape shifting house that is a character in itself. These unnervingly sensual acoustics aid the DoP's extreme closeups, which create an awkward, uncomfortable atmosphere. The performances are good, too.

The problem is quite simply this - what on earth is it all about? Well, Aronofsky says his story is drenched in biblical references, but these complexities are only fully apparent to those who have either read Aronofsky's artist statement or are well versed in the good book. It's also been said that 'Her' represents mother earth while the rest of the characters represent the threats to our planet. This is the kind of over reliance of pseudo-profound metaphors rather than complex, believable characters and narrative that really turn me off. It's better to ignore Aronofsky's self- indulgence and see it for what is - a massively inferior homage to Rosemary's Baby with a semi-interesting metaphor about selfish masculinity at its core.

Now the theme of self-absorbed, self-pitying masculinity could make for a very interesting film, but any possible resonance is lost when a filmmaker communicates this subject through a litany of chaotic metaphorical surrealism.

The reverse is true of Rosemary's Baby, which is rooted in chilling reality with an endearing central performance by Mia Farrow, whose relationship with John Cassavettes's character is human and romantic. The relationship between 'Mother' (Jennifer Lawrence) and 'Him' (Javier Bardem), on the other hand, is bereft of development; we barely even see them communicate. You could argue that this is because 'Him' represents male self-absorption, but it's difficult to empathise with a couple that have such an odd lack of chemistry.

This dubious central relationship quickly receives even less attention as 'Him' entertains a gradually increasingly large group of hateful strangers who further harass and use 'Mother'. Her treatment caused me to feel some degree of indignation, but I didn't genuinely care because mother! amounts to little more than a sequence of pretentious allegories and metaphors. It's just like watching a bad dream, and dreams don't have the tangibility and resonance of reality.

I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Its message is blunted by blatant emotional manipulation

This grim realist drama succeeds in putting some humanity into the austerity/benefits debate, but Ken Loach undoes the impact of his polemical film with simplistic emotional manipulation. Indeed, Loach's agenda interferes and reduces his storytelling to mere melodrama at least twice.

Take the scene in which a starving Katie visits a foodbank; she is surrounded by fruit, bread and vegetables, yet she messily eats cold beans out of a tin and bursts out crying in shame. Why would she eat this when she could choose food that's far easier to eat? Because Ken Loach wants us to feel bad, that's why.

And then there's the ending, which sees Daniel and Katie meeting with an adviser who's confident that he can win his appeal. However, just as the film's mood starts to finally buoy, Daniel keels over and dies in the bathroom. Predictable, very predictable. It's surprising that a veteran director like Loach would use such formulaic emotional manipulation.

Dunkirk (2017)

Dunkirk lacks the character development to be in the pantheon of great war films,

There is an engrossing immediacy about Dunkirk, you are thrust into the action and the grip seldom loosens. It is pure action, pure cinema. The problem with this is that there is little plot and little characterisation, so the impressive spectacle does get slightly repetitive at times. This could have easily been a two-and-a-half hour picture, so there was certainly room for greater character development. It wouldn't be excessively negative to say that this was something of a missed opportunity.

Chariots of Fire (1981)

The biggest piece of Oscar bait to ever win Best Picture,

This is a vanilla piece of cinema - classic Oscar-bait. Every character is a blue- blooded bore apart from Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), a zealous Scotsman who refuses to race on a Sunday. This, believe it or not, is the central conflict of this bland British classic, the dramatic peak.

Many will enter Chariots of Fire expecting dramatic, slow motion running to that iconic score by Vangelis, and that is what they will get in the opening five minutes. However, they'll have to go through about 100 minutes of dinners, sermons and received pronunciation until Harold's Olympic sprint, which finally breathes some life into the film by skilfully wracking your nerves.

Even if the slack narrative was tightened up, the importance or interest of this story is dubious at best. Where's the drama, where's the sacrifice? There is none.

Baby Driver (2017)

Little more than a mix tape with dull characters and clichés attached to it

I read an early tweet that described Baby Driver as 'a mix-tape with a film attached to it' and that proved to be an accurate comment. The tweeter may have thought this was a good thing, but I certainly don't.

Yes, there are some good tracks and the action sequences are elaborate and frenetic (a little too frenetic, actually), but the characters are dull, unlikeable and bear very little relation to the real world. I simply did not believe in them, especially Darling, the sassy, kick ass stock character that only a fool would consider to be a strong female character.

Then there's Baby, whose laconic, boyish demeanour makes him a rather uninspiring protagonist. His romance with Debbie, a cute little waitress, is yawn-inducingly clichéd, too.

If you want a stylish heist film that isn't so bloody try-hard, then watch Drive. It's an exercise of style over substance much like this film, but it has suspense, atmosphere and characters that could actually exist rather than blaring music, mind-numbing action and flat, hateful comic book characters.

Logan (2017)

Hack, slash, stab, repeat.

Logan certainly delivers in terms of hacking, slashing and stabbing, but the wounded bear routine of the titular character wears pretty thin. Logan is the antihero stock character very much in the brooding, world weary style of John Rambo. The zenith of the cliché occurs when Logan remarks that familiar tortured line: 'Everyone I care about gets hurt'. Jackman does transcend the limitations of his character with moments of raw emotion, but these are few and far between.

The rest of the performances are fine, passable; although I would have liked to see Richard E. Grant chew some scenery. If you're going to cast a British baddie, let him go full blown Gary Oldman - what this bleak spectacle sorely needs is some charisma.

Alas, the bland characterisation isn't saved by the narrative, which follows a monotonous cat-and-mouse formula that's bereft of any suspense. A viewing of 'No Country For Old Men', a preeminent cat-and-mouse film, will remind you just how tiresomely loud and noisy 'Logan' is.

What we have then is a dumb and decidedly average action film with a filter stripped right from Johnny Cash's 'Hurt' video and a litany of brutally repetitive fight scenes.

Green Room (2015)

Green Room is light on story but excruciatingly heavy on blood spattered, genre-leading survival thrills,

Director Jeremy Saulnier knows a thing or two about set pieces. Head shots, too. The harrowing events of Green Room occur in just several rooms, yet Saulnier's stripped- down script and direction creates a veritable white-knuckle ride of desperate reversals of fortune and shocking explosions of violence.

The victims of all this nastiness are The Ain't Rights, a struggling Punk band comprising Pat (Anton Yelchin), Sam (Alia Shawkat), Reece (Joe Cole) and Tiger (Callum Turner). After stealing some petrol for their battered old camper van, they head to Seaside, Oregon, where a local DJ arranges a gig for them at a 'right-wing' venue, an offer which the destitute band cannot afford to decline.

When they arrive at the club - which is in an ominously remote corner of the Pacific Northwest - the shaven heads, tattoos and sketchy, leering glances make it clear that the crowd is not merely right-wing but positively fascist. It is at this moment that a feeling of palpable danger and isolation starts to germinate, a feeling that comes to brutal fruition when Pat is witness to a murder in the club's green room.

In a hail of panic and confusion, the band and Amber (Imogen Poots) are locked in the room under the guard of Big Justin (Eric Edelstein) and his fully loaded Smith & Wesson .500, which he explains has cartridges so large that only five can fit into the cylinder. What ensues is a savagely intense siege that affords both its protagonists and the viewer very few luxuries.

After the first few instances of jarring violence, I feared that the film was going to be ninety minutes of audience punishment in the style of The Loved Ones or Wolf Creek. Thankfully, the fortunes of our besieged protagonists do improve, albeit in a wayward and unpredictable manner. It is all the better for it too - the twists and turns of the band's seemingly insurmountable predicament had me in a choke hold until the very end.

What makes Green Room so engaging is its relatability; it is much like Deliverance in this respect. Both films thrust normal people with little experience of violence into a lethal situation, causing the viewer to wonder 'what would I do?', 'where would I be in this group's dynamic?'.

Similarly, the protagonists of both films have no one to turn to, no outsider that they can fully trust. With his smooth diction and measured disposition, Darcy (a very interestingly cast Patrick Stewart) initially appears to be a mature voice of reason amongst a pack of rabidly aggressive young men. Alas, such hopes do not last as the contrary becomes quickly evident. It is only Gabe, played by Saulnier's childhood friend Macon Blair, who appears to be someone the band can work with. Blair channels much of his performance through an anguished gaze that reveals shades of anxiety, doubt and shame. It seems that Gabe has fallen prey to Darcy's steely manipulation.

This is about as dynamic as the characterisation gets, because although Green Room features fine performances across the board, it is a film that's driven by genre-leading survival thrills rather than plot and characters. If you choose to go and see it - prepare yourself!

High-Rise (2015)

High-Rise's allegory of class divide gets lost in a dull montage of blood, sweat and blue paint

Ben Wheatley is one of the most exciting British directors working today. His two best films are Kill List, a deeply disturbing horror/thriller about a tormented contract killer, and Sightseers, a black comedy about a troubled couple on their parochial, psychopathic honeymoon.

Key to these films' success are strong characters with interesting dynamics. Kill List begins almost like a domestic kitchen-sink drama centred on the failing relationship between Jay (Neil Maskell) and Shel (MyAnna Burning), but it subsequently evolves, or rather devolves, into something dark, dank and horrible in a most unpredictable manner. Sightseers may be most commonly remembered for its scenes of outlandish violence, such as when Chris (Steve Oram) deliberately runs over a litterer in a fit of righteous anger. However, underneath the comic outbursts of gore is the poignant relationship between Chris and Tina (Alice Lowe), an oddball pair with a past of loneliness and insecurity.

Having proved himself as a director of visceral horror and emotional substance, Ben Wheatley is the natural choice to direct J. G. Ballard's High-Rise, a Goldingesque tale of violent class war exploding within a brutalist tower block. The fragility of civilisation, and the primitive savagery that lurks beneath it, is a darkly fascinating subject that has made for excellent films and books, such as Threads, a devastating vision of post- apocalyptic Britain, and William Golding's Lord of the Flies, which needs no introduction.

High-Rise does not brush shoulders with such works, for its allegory of class divide gets lost in a dull montage of blood, sweat and blue paint. Oh, and dancing air hostesses, for reasons that are, to put it politely, enigmatic.

The focal characters - Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston), a measured, middle class doctor; Charlotte Melville (Sienna Miller), a sultry woman who serves as Laing's gateway in to upper floors' high culture; Richard Wilder (Luke Evans), a pugnaciously aspirational documentary maker; and Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons), the patrician architect who designed the building - are introduced well enough, but ultimately do not receive sufficient development.

As the lead and perhaps most relatable character, we are in the body of Laing when he traverses the tower's social scene, which he admits to 'not being very good at'. Some may find him steely, but Laing has an affable reserve and high emotional intelligence. He isn't particularly interested in the petty one-upmanship that comes with climbing the social ladder, but he manages to deftly negotiate it anyway through his insouciant reserve that maintains peoples' interest and disarms any potential enemies. Hiddleston, one of Britain's hottest exports, is well cast here, he delivers the best performance of the film.

However, after a competent introduction to society in the high rise, Laing and the others get lost in an incoherent narrative that favours aesthetics and absurdity over credible character interplay. It begins three months ahead of the main events, showing a blood spattered Laing roasting a dog's leg over a fire surrounded by dirt and detritus. After the introductory period of around thirty minutes, the film then charts what led to this repellent spectacle with a disjointed series of set pieces that give little sense of progression.

Electrical problems are plaguing the building and resentment is brewing between the upper and lower floors, but the descent into nihilism just happens. Dogs are being drowned, Laing's painting his apartment (and himself) like a total madman and the whole building becomes a rubbish-strewn nightmare - but there's no tension, no crescendo, no credibility and, curiously, no one who considers leaving! The worsening relations should have been more gradual and given much greater depth and meaning by the characters, their dialogue and their relationships. Instead, the main character covers himself in paint to communicate his increasingly aberrant state of mind, which appears to be an obvious metaphor for tribal decorations.

High-Rise fails as a film about primal savagery and particularly as a film about class. In Woody Allen's Blue Jasmine, I cringed as Jasmine and her husband Hal, arrogant members of New York high society, barely contained their raging superiority complexes as they awkwardly condescended to Ginger (Jasmine's sister) and Augie, a decidedly blue collar couple who wonder at Hal and Jasmine's luxurious home. No such realist interplay is to be found in High-Rise, because its characters are thinly drawn and it isn't rooted in reality, which is very much to its detriment.

Towards the film's end, there are moments in which Royal and his minions discuss the politics and future of the tower, with Royal remarking that the lower floors should be 'Balkanised', meaning that they should be fragmented and pitted against each other in a manner reminiscent of the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. I liked the use of that phrase, there should have been a lot more of this in the script, more overt political manoeuvring rather than surrealist claptrap and brutalist 70s chic.

Alas, Wheatley's High-Rise is more concerned with aesthetics and the 1970s, which means there's more in the way of shag-pile carpets, dodgy hair and the colour brown than developed characters, coherent narrative structure and sociopolitical substance.

Nightcrawler (2014)

Jake Gyllenhaal gives an excellent performance as Lou Bloom, one of the most compelling on-screen manipulators I've seen in a long time.

Nightcrawler is a Schraderesque character study of a man far more dangerous than Travis Bickle. Like Bickle, Lou Bloom doesn't like people, however Taxi Driver saw Bickle feel compassion for at least one person, Lou seems to have contempt for absolutely everyone. Lou's interactions with other people have only one purpose - control. He is very opportunistic and has an unshakable confidence that isn't hindered by the human inconveniences of nervousness and guilt.

Jake Gyllenhaal commands the long monologues of Dan Gilroy's script, stealing every scene he's in as the unnervingly brazen and enthusiastic Lou Bloom. Gyllenhaal lost 20 pounds for the role and it really worked, his gaunt face and glaring eyes do quite a lot of the acting for him. The performance carries the film and this will no doubt be recognised by the Academy next February.

In the film's opening moments, Lou is a vagrant who is shown committing crimes both petty and, it's suggested, not very petty at all. He's in the desperate pursuit of a job, and when he meets someone who could be of benefit, Lou initiates his charm offensive and inundates them with a relentless barrage of articulate yet platitudinous language as if he's reciting the effusive CV of a quixotic student.

Although his self-promotion is overbearing in the first few instances, Lou soon proves his skill in accruing large amounts of information and repeating it with the utmost conviction and credibility. Gyllenhaal must have relished delivering director Gilroy's excellent script; his manner of speech reminded me of Patrick Bateman's highly detailed monologues on everything from his morning routine to Huey Lewis and the News in Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho. Despite both men's articulacy, their diction feels recycled, and this is because it is - their cynical sociopathy means they cannot form true, sincere relationships, but they are able to counterfeit them through their adroit ability of learning and imitating the necessary behaviour.

Quick wits and amorality are key skills for any successful paparazzo, so it is unsurprising that Lou Bloom thrives in the field. His first forays into professional prying are very funny. Inspired by a chance encounter with venerable camera man Joe Loder (Bill Paxton), Lou buys a rudimentary camcorder and scours the myriad streets of Los Angeles. Abruptly stopping next to the scene of a car accident and poking his camera right in people's faces. When he's challenged he proclaims with an uncommon doubtfulness -'I'm fairly certain I'm allowed to do this!' You soon see Bloom gain confidence as he pushes the boundaries further and further, making for tense and unpredictable viewing.

His audacity proves successful, snatching footage that's nice and gory, impressing Nina Romina (Rene Russo), the blonde, brassy director of a local news channel. Despite an appearance and demeanour that suggests seasoned business acumen, Nina spends much of the film under the thumb of Lou.

After proving his worth, enjoying his growing control over Nina and soon realising how vital he is in maintaining the news agency's spiking ratings, Lou proves that his manipulation can work, albeit it very unattractively, in courtship. Gilroy's best monologue occurs when, over dinner with a reluctant Nina, Lou blackmails her into establishing a longstanding sexual agreement, using a business-like vernacular bereft of anything remotely romantic, erotic or sexual.

Like Gone Girl, Night Crawler is a satire of the yellow journalism peddled by television news, content that's perhaps interesting for the public but not in the public interest, a distinction that is gleefully ignored in favour of lucrative scare-mongering and countless other immoralities. As the majority of the characters are under this satirical gaze, I found it hard to care when they fell victim to Lou's vicious conniving, my apathy even extending to his long suffering accomplice Rick (Riz Ahmed), who is too darn wet and spineless to get that emotionally invested in. None of this, I hasten to add, is a significant detriment, if a detriment at all.

The film is attractively shot by Robert Elswit, much of whose striking work can be found in the films of Paul Thomas Anderson including There Will Be Blood (2007), Punch Drunk Love (2002) and Boogie Nights (1997), the latter's sun-kissed, neon-lit aesthetic being most similar to Nightcrawler's. Elswit's work here is also likely to draw comparisons with Newton Thomas Sigel's photography in the beautifully slick Drive (2011).

With a tense, unpredictable narrative that's laced with strong satire and anchored by a great character and great performance, Nightcrawler is one the best films of 2014.

The Riot Club (2014)

A genuinely uncomfortable, shocking film about yobbos in waistcoats that met and surpassed my expectations

After an amusing introductory scene that informs you of the club's centuries' old origin, the film turns to contemporary Oxford and presents us with the latest generation of students and Riot Club members. It follows first-year students Miles Richards (Max Irons) and Alistair Ryle (Sam Claflin), both are of 'good stock' but the former is normal and down-to-earth and the latter is a malicious, fascistic sociopath.

During the fresher's activities, Miles quickly befriends the middle- class Lauren (Holliday Grainger), a friendly girl from Northern England; the romantic pair have a sweet naturalism as they playfully talk about and erode their differing heritages. The scowling, aloof Alistair however proves to be not much of a conversationalist.

Both are soon inaugurated into the Riot Club, whose other members include Harry Villiers (Douglas Booth), the pretty boy who struck me as the de-facto leader of the club; Hugo Fraser-Tyrwhitt (Sam Reid), a closet homosexual with an attraction to Miles; Dimitri Mitropolous (Ben Schnetzer), a horribly rich Greek student, and James Leighton- Masters (Freddie Fox), the smug little squirt who's somehow the president of the club. Some have said that it is littered with caricatures, however the film isn't about ordinary Oxford students or ordinary privilege, it is about an elite circle of extreme wealth and aristocracy.

After Miles and Alistair make up the Riot Club's ten members, the group soon have their risibly pompous suits tailored and set off for a night's debauchery to The Old Bull, one of the few establishments they haven't been banned from. By the time this happens, I thought I had the measure of the pretentious characters and the film's narrative and tone, however as the 'dinner' progresses, both the characters and the course of events become veritably loathsome.

As most will know, The Riot Club is inspired by the Bullingdon Club, an Oxford University dining society infamous for its destructive hedonism that boasts alumni such as David Cameron, Boris Johnson and George Osborne. The film's main target of attack isn't the purported anti-social behaviour of such people, the obnoxious decadence we witness is not endemic to the highly disagreeable 'Riot Club', what it attacks is rather the characters' raging, blue-blooded superiority complexes that causes it. Some may disagree with its politics, they may consider it a gross exaggeration; it is indeed vehement in its depiction of class wars, however I think it is undeniably a very well executed piece of filmmaking.

The film is adapted from the stage play Posh by Laura Wade, and the middle section of the narrative, which is one long scene, certainly feels like the work of a playwright. Like Tracy Letts' Killer Joe (2011) and Bug (2006), it is another example of how punchy stage material often makes an excellent transfer to the cinema.

Much like Letts' work, The Riot Club contains a maelstrom within a cramped four walls; the scene goes from embarrassing to plain excruciating as the decuplet, fuelled by alcohol, drugs and each other's presence, become increasingly hateful and immoral, the vile crescendo eventually reaching a climax that's genuinely shocking. It is all witnessed by the unassuming pub landlord. He is initially honoured to host the boys, the sight of him sycophantically at the beck and call of people half his age who look at him the way they would dog mess on their shoe is pathetic in the true meaning of the word.

The worst offender is Alistair, Sam Claflin is excellent when delivering his well-written diatribes with drunken, acerbic hatred. Alistair's genocidal contempt for the working classes and those bereft of prestige bore similarities to Adolf Hitler's loathing of Jews; he gets so angry that he's reduced to saying 'I'm sick to f*cking death of poor people!' Alistair is the most odious example of unearned privilege and arrogant sense of entitlement, he rants about the successes and innovations of the ruling classes and the proletariat's supposed jealousy as if he's had a part in it, after all, what exactly has he achieved apart from winning the genetic lottery? Claflin proves himself as an accomplished villain actor, he gives his character a sociopathic quality; when there aren't flashes of his vulgar jealousy, resentment and massive hubris, Alistair has an unnerving emotional vacuity.

The Riot Club is not simply 107 minutes of pretty boys holding champagne flutes, it is a sharply made thriller that is perhaps politically divisive but rivetingly executed.

Joe (2013)

Nicolas Cage disappears into his role as the titular Joe in a film that's thematically rather familiar but also a surprisingly realist piece of cinema.

The film follows the principal characters Joe (Nicolas Cage) and Gary (Tye Sheridan). Gary is the only member of his degenerate family who is able to work and earn a living. He has been forced to become a responsible person by his vile, repulsive father Wade (Gary Poulter), a man who has abused his body so much and for so long that he can only speak in slurred, incoherent ramblings. I recently compiled a list of the 10 most hateful characters of cinema - I think Wade could quite easily be placed in it.

Joe is a recidivist who is haunted by his criminal history and continues to struggle with controlling his anger, it seems the only way he can stay out of trouble is by absorbing himself in his small landscaping company.

Joe leads a group of black workers, they clear wooded areas with these rather strange axes that waywardly squirt poison everywhere. Joe and Gary are brought together when the boy implores him to employ both himself and his father. Joe obliges and Gary proves to be a good worker, although the agreement is soon thwarted by his obnoxious father who is too polluted, weak and lazy to contribute to the team.

The cast of Joe's workers and indeed the whole film is populated with actors who were seemingly taken from the street, their performances are completely natural and their language raw, colloquial and as a result sometimes completely incomprehensible! A few times I felt like an American watching Trainspotting, particularly during a row between the moronic Wade and a black worker, whose ebonics is the strongest I've ever heard.

Joe is a tough watch, there are characters that represent the very lowest form of human life, there's seldom a room in the film that isn't a filthy, cluttered mess. I didn't expect it to be such a realist piece of cinema, its depiction of blue collar work and young Gary's first foray into it is sure to resonate with anyone who's had similar experiences, myself included.

Nicolas Cage doesn't stick out at all, he effortlessly blends in with the surrounding cast of largely unknown actors. Like Leaving Las Vegas, Joe is an example of Cage moderating his idiosyncratic acting, which I like incidentally, and showcasing just how good he is.

Clear correlations can be made with Mud, a similarly themed film about a benevolent renegade forming a bond with Tye Sheridan's conflicted teenage boy. Joe is the superior of the pair, although Mud boasted good performances from its leads, it was melodramatic and overrated. Tye Sheridan's character Ellis in Mud, who is given far too much screen time, thought about love and human relationships in ways that 14-year-old boys just don't - I didn't believe in him. He also had a habit of vehemently punching people in the face that belied his prepubescent little frame. Joe's Gary is a much better character, a measured boy who simply wants to make a living and prove to the men in his life that he's no kid.

Mud lacked Joe's gritty nastiness, it had treacly melodrama instead of stark reality. What they do share is the running theme of redemption, and in the case of Joe, I found its conclusion rather familiar and subsequently bathetic. Despite this, Joe succeeds in absorbing you in its masculine world and Nicolas Cage defies any naysayers by completely disappearing into his role as the titular rogue.

Good Morning, Vietnam (1987)

A dull, predictable film that's merely a vehicle for Williams's tediously overbearing comedy.

There's a great Family Guy cutaway gag in which Peter Griffin and Robin Williams sit on a sofa as Peter names topics such as religion and politics for Williams to comment on. Williams does so with his trademark brand of insufferable overbearing comedy, which is filling any amount of time with frenetically incessant rambling. Peter responds simply with an exasperated sigh before leaving for a five minute break, which prompts Williams to start yet another barrage of supposedly funny noises. I felt much like Peter Griffin whilst watching Good Morning Vietnam. It reaffirmed my opinion that Williams was not the 'tragicomic genius' that so many purported him to be.

Read a short synopsis of Vietnam and you'll know exactly what it's all about: the lovable family favourite Robin Williams being kooky, charming the troops but clashing with straight-laced, humourless authority figures. It's completely predictable and completely trite. They also throw in a love interest for good measure in the form of Trinh (Chintara Sukapatana), a wholly lifeless woman whom Williams refuses to stop pestering.

Williams is never funny during his radio broadcasts, however the film repeatedly tells us otherwise, showing us scores of characters struggling to hold back their tears of laughter. So many of the supporting actors, whether they're random troops or studio operators, were just diegetic canned laughter rather than proper characters.

Make no mistake, Robin Williams isn't playing Adrian Cronauer, he's playing Robin Williams at his most loud and rambling. Williams is repeatedly characterised as the lovable clown who brings the people together, it's rather nauseating; no matter how hard the film tries, it cannot convince me that he's either funny or charming, only very irritating. Despite this, there are some moments that raised a smile, such as the language class scenes in which he focuses on New York City street talk rather than the artificial, staid sentences of the textbooks.

Williams's flatly developed adversaries Lt. Steven Hauk (Bruno Kirby) and Sgt. Major Dickinson (J. T. Walsh) are the typical officious military men, they develop a resentment towards him that's so instantaneous that it's contrived and unbelievable; they're just narrative functions that try and make you feel sorry for Williams the lovable crazy cookie.

It sometimes attempts to be a drama or 'dramedy' with moments of perfunctory war moralising, but ultimately Good Morning, Vietnam is preoccupied with indulging Williams's penchant for shouting incessantly rather than achieving anything approaching credible commentary or pathos.

Jesus Camp (2006)

I objected to so much in Jesus Camp that it's hard to know where to begin.

Jesus Camp follows a group of children as they're indoctrinated by fundamentalist Christians at a summer camp; it is a documentary that leaves one both angry and incredulous.

At the centre of it is Becky Fischer, a fat, obnoxious egotist who serves as the main speaker at the camp. We see Fischer preaching emphatically to these young minds, permeating their innocence with fear and guilt until they cry hysterically. So ridiculous and damn risible is her fanaticism that she even condemns Harry Potter, spouting that 'Warlocks are enemies of God! Had it been in the Old Testament Harry Potter would have been put to death! You don't make heroes out of warlocks!' - clearly, a religion of peace.

What is happening here is not religion, it's child abuse. The children aren't given the opportunity to think for themselves, they are inundated and imbued with bigotry, absurd reactionary values and a completely zealous devotion to God. Fischer and her creepy minions are quite open about what they're doing, she even refers to it as 'indoctrination' in one instance, but they see nothing wrong in it, in fact she even says - 'I would like to see more children indoctrinated!' When asked why she targets children, Fischer replies candidly and without shame - 'The reason that we target kids is that whatever they learn by the time they're 7, 8, 9 years old is pretty much there for the rest of their lives.'

Much of what you see is deplorable, but it truly passes a boundary when the indoctrinators use the language of violence, speaking of things such as 'God's army', 'fighting' and 'war'. After many children have been driven slightly mad by the suffocating mania of Fischer and her misfits, they are encouraged to pick up a claw hammer and manifest their religious zeal into violence by smashing mugs that represent all things satanic.

It's this 'God's army' mentality that produces the most disconcerting behaviour amongst the children. One child speaks of how she feels like a 'warrior' and that she's at 'peace' with death; her point is expanded upon by 12-year-old Levi who says - 'you know a lot of people die for God and stuff and they're not even afraid.' It is not only entirely abnormal for children to contemplate their mortality like this, but also a scary indicator of what could happen if America's political landscape was to descend into bedlam - I could see this pernicious, insane devotion to God becoming very violent indeed. They claim that their cause is purely spiritual, but that is nonsense, the real purpose of their dogma is to create a Evangelical overhaul of the government.

All of this incessant madness and irrationality is interrupted sporadically by Mike Papantino, the Christian co-host of radio programme Ring of Fire. The camera captures Papantino in his studio as he articulately despairs of these people, highlighting the alarming scale of the Evangelical movement and how this affects the democracy of the United States. Although I disagree with his religious views, Papantino reminds the viewer that there are normal religious people out there that believe in the separation of church and state just like the founding fathers of their country.

Despite the input of Papantino, the documentary is, to its credit, largely impartial. Directors Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady just let the cameras roll on their unhinged subjects; to insert their presence into the documentary and make any judgement would be unnecessary. Jesus Camp is an important insight into the deeply troubling Evangelical underbelly of the United States.

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

This film is not a glorification, it's an observer rather than a judge

The Wolf of Wall Street is a rather straight forward rise and fall story, it's 'Scarface' with even more excess but without the M16 with an under-slung M303 grenade launcher.

Some have said that this film is a glorification rather than a satire, a three hour parade celebrating Jordan Belfort's excess instead of a stern condemnation. Despite all the drugs, decadence and vulvas in the film, I don't think the film glorifies him, and I don't think it's a biting satire either.

The film is an observer rather than a judge; it displays Belfort and his minions' debauchery in a grand three-hour narrative with the energy and gusto of 'Goodfellas', letting the audience decide what they think of it all. If one leaves the theatre impressed or inspired by Belfort, that's very much a reflection of them rather than the film.

There is a lot of bad behaviour going on in The Wolf of Wall Street, understandably too much for some people, but over the course of three hours I didn't find it exasperating like some have. In fact, I think one would possess a certain amount of sanctimony to deny that there isn't a degree of allure to Belfort's lifestyle; an element of excess should be everyone's life, whether it's occasionally ordering that £30 sirloin steak or at some point in your life owning a car that does 20 miles to the gallon, just because it makes you feel good.

Of course, that wouldn't begin to be enough for Jordan Belfort. His ideas on money, relationships and life in general were quite awful during his years at the helm of Stratton Oakmont, his company that employed the 'pump and dump' scheme to rob scores of investors of their money. It is Belfort's obsession with wealth, material goods and just winning that makes him quite a one-dimensionally unpleasant character. The nature of the character made me question the casting of Leonardo DiCaprio.

This is not to say DiCaprio is in bad form here, his performance is teeming with conviction. Leo is in his element during Belfort's rousing, maniacal speeches to his employees; his frenetic energy reminded me of Evangelical preachers found in the southern states. Of course, there's nothing remotely Christian to be found in Belfort's fervent rhetoric, only sentences of remarkable crassness, immaturity and myopia – 'Does your girlfriend think you're a f*cking worthless loser, good! Pick up the phone and start dialling! I want you to deal with your problems by becoming rich!' – 'If anyone here thinks I'm superficial or materialistic, go get a job in f*cking McDonald's because that's where you f*cking belong.'

Despite DiCaprio's committed performance, I'm not part of the indignant crowd who demand that he finally win the Oscar for best leading man, particularly with this year's nominations. He's had a great career so far, he's worked with Hollywood's most revered artists and has had a consistent stream good roles. Although his performances regularly display his great dramatic range, the problem is his huge Hollywood profile, I feel like I'm watching Leonardo DiCaprio rather than the character he is portraying. It's the same with The Wolf of Wall Street, Leo is just too cute and popular to play someone like Jordan Belfort – the casting gives a certain amount of sheen to him. Also, DiCaprio didn't adopt Belfort's New York accent, which is a pity because Leo's South African accent in Blood Diamond was impressive.

While there are flashes of gross vulgarity in DiCaprio's performance, the real Jordan Belfort is worse. To his credit, he is a naturally adroit salesman, he ran a successful meat business in his early twenties, he could've probably made a substantial legitimate living with his innate entrepreneurialism. However he didn't, and now he remarks in interviews and speeches that 'making money is easy', what he forgot to add is '

when you broke the law like I did'. I'm not preaching here, I'm just reminding the crowds he draws to his motivational speeches that this man's immense wealth hinged completely and utterly on criminality.

The other reason why Scorsese's Belfort isn't hateful enough is because the repercussions and victims of Stratton Oakmont are never shown, and to give a properly three-dimensional depiction of Belfort's story, they should have been. Scorsese and writer Terence Winter have followed Belfort's memoir so closely that it's quite a one-track narrative, perhaps they could have stepped back from the book and explored the extent of Stratton Oakmont's damage.

So, it is clear that there's not a particularly complex figure at the centre of Martin Scorsese's latest film, but that certainly doesn't mean it's a misfire. This is 'Casino'/'The Departed' Scorsese rather than 'Taxi Driver'/'Goodfellas'/'Raging Bull' Scorsese.

For me, the film's terrific energy and vibrant aesthetics manage to carry its three-hour running time. Among this spirited, flashy spectacle are also some very amusing moments, particularly Matthew McConaughey's great performance as Mark Hanna, a veteran stock broker who teaches an up-and- coming Belfort about his new profession, from ethics to the necessity of masturbation. What's become one of the larger talking points of the film is the sequence where Belfort, overdosing on Quaaludes and in a state he calls the 'cerebral palsy phase', tries desperately to drive his Lamborghini Countach back to his enormous house.

Although the one-dimensional central character and its limited perspective means it is not Scorsese's best film, The Wolf of Wall Street is an engrossing, sweeping rise and fall tale that is vibrant, funny and very striking.

www.hawkensian.com

Get Carter (1971)

'Get Carter' is certainly an icon of British miserablism, however my most recent rewatching left me unimpressed

I love British films of the 60s and 70s. Everything's very grey and very brown and the characters are thoroughly downbeat and pessimistic; there's also vile patterned wallpaper everywhere. The visceral kitchen sink drama is a British trademark that can still be found in later films such as Gary Oldman's 'Nil by Mouth' (1997) and Paddy Considine's 'Tyrannosaur' (2011).

'Get Carter' is an icon of British miserablism, I first saw the film on TV when I was quite young, I liked it. I've had it on DVD for years and always regarded it as a nasty, hard hitting classic. However, after watching it again in 2013, I was left rather deflated.

There's no doubt that it continues to be drab and nasty. The abject horror of 60s architecture can be seen throughout the film; I think the brutalist architects of the 50s and 60s did more damage to our landscape than the Luftwaffe. 'Carter' really corroborates the saying 'It's grim up north', as the film's great climax shows that even the beaches can't escape the polluted, achromatic hell of the city. (I'm pleased to see that the beach has since been completely cleaned up)

Despite this, the problem at its core is simply age, it has dated badly. The violence has no punch, quite literally; the choreography of Caine's beat-downs on various enemies is unconvincing and in some instances just risible. The worst example of this is when Carter manages to catch someone's fist and slap him round the face in a scene that is horrendously edited. There's also another moment where he lunges towards a woman (who cannot act) in a café and wraps his hand around her throat in a highly orchestrated fashion.

All of this amateurism is exacerbated by how, in this film at least, Michael Caine is not an intimidating figure. In 'The Long Good Friday' (1980), Bob Hoskins is short, stocky and has a very bad temper, however Caine, whilst cool and moody, is rather lanky and weak.

The script is also dated, it's all 'bloody' this and 'you're a git' that. While there's no doubt that the British have an affinity for such words, it felt like the script was under the gaze of Mary Whitehouse (Well, someone more lenient actually, the ridiculous Whitehouse would even object to the lexicon of Get Carter)

Aside from its age, I also found the story weak. It is basic, which can be great, however as the characters and their relationships are so unremarkable, Carter's straightforward revenge narrative suffers. I didn't particularly care for Carter and his cause, he's a blandly nasty character meting out justice to other equally flat characters.

Caine is fine as Jack Carter; he has moments of great anger, especially in an emotional outpour in the film's final minutes. Outside of these moments however is a rather standard hard man stock character performance.

While 'Get Carter' is still bleak and perhaps captures the zeitgeist of 70s working class Britain, it is rather dramatically unaffecting. After years of thinking it was a great film, I was left unimpressed by its lack of character development, its collection of poor supporting performances and its dated action and script. The shocking climax on that foul, polluted beach and Roy Budd's fantastic score are still high points, though.

69%

www.hawkensian.com